26 October 2006

19 October 2006

Glenn Gould : au-delà du temps

Documentary by Bruno Monsaingeon (France/Canada, 2005, 1h07mn)

13 Octobre 2006 20h30 Auditorium, Musee du Louvre

Glenn Gould plays Bach

Credit: vagifabilov (Norway)

This clip of the young Glenn Gould at practice shows his two most vivid qualities as a pianist -- a genius and an eccentric. Look at the way he hums, the way he moves his hands and his whole body, the way he places his piano, the way he puts his legs, the way he dresses, the way he searches for inspiration, the way his emotions overwhelmed him, the way his fingers flies on the keyboard, the way he stops his practice... nothing is "orthodoxical" as the rules for a classical pianist, in particular, his low position to the piano and his peculiar body movements. He was recognised as one of the greatest pianist of the 20th Century at a young age, but the canon rejected him for the fear of breaking down the so-call "system", another old story in the development of modern and contemporary arts.

Glenn H. Gould (1932 – 1982) is famous for his unique interpretation of Bach's Goldberg Variations. This Canadian pianist loved to hum while he played, his recording engineers once proudly explained how successfully he was able to exclude his voice from his recordings. These hummings for Gould are subconscious singings, and increased proportionately with the inability of the piano in question to realise the music as he intended. In another word, his voice becomes part of the music compensating the techinical problems of his piano.

When he plays, no matter in live performance or in recording studio, he has to bring with him his old chair his father had made even when it was completely worn through. This chair is so closely identified with him that today it was covered in a glass case and is in display in the National Library of Canada.

This genius gave up live performance at the age of 32 (in 1964) and concentrated on studio recording, simply because his piano music is not only for the audience to listen to, but to watch and listen to and move with. That’s why we can see him playing today. It is said that Gould would never play a piece the same way twice. His favorite is Bach, when he plays Bach, it’s not him who’s playing, but Bach himself comes to life. In the documentary, he says while playing The Art of Fugue, "this note is a mistake. Bach would have amended it if he were still alive."

Here comes the most beautiful interpretation of Bach's Goldberg Variations recorded in around 1981. Are you ready for an awesome moment of trance?

Glenn Gould plays Goldberg Variations Aria & var.1-7

Credit: opus3863 (Japan)

18 October 2006

Why not English -- On French as a language (4)

What was France doing at that time? France was first under Napoleon III in the process of Haussmannization of building grand boulevards and glittering cafes, and later the building of the Third Republic. It was all about being "Frenchy", a tag for cultural and identity pride.

Thanks to the Sun King, French had long been the "official language of Europe" unbeatable even by the British Navy. When the cook sportif woke up the country, the American diplomats were already standing in the Hall of Mirror demanding the 1919 Treaty of Versailles to be written in English as well, making the treaty a first in roughly 500 years of European history to have an English version. Should Jacques Chirac had been there, he would have said "No!" to the Americans. Earlier this year, this die-hard advocate of French (against English) stormed a EU meeting because his fellow Frenchman, Ernest-Antoine Seillière, chose to speak English. Why? Because "such snobbery from the leaders of some international companies to speak only the American business language is intolerable."

To the non-French-speaking tourists, Paris is "intolerable"-- no English signs, no English menu, no English local newspaper, no English chanels, no English broadcast...These are absent in the defense of French as a language. The French society and education environment don't encourage English. In scientific and medical researches, for example, France insists on publishing in French, this resulted in a great gap between the country and the world. New adventures and important discoveries remain unique to the francophone countries and incomprehensible to the outsiders. On the other hand, translation is quick to catch up the world trend. Almost all literary work published in other languages, including English, will soonly be translated into French. There is an efficient division of labour, the experts are doing the job so we people don't need to harsh ourselves to read English... even those "elite" students from l'ENS or la Sorbonne choose French translations than English originals, despite the fact that they are Postgraduate researches in the English Department.

However, it doesn't mean the French refuses to speak English. Once the students joined in the workforce, especially in the commerce, they know they have to deguise themselves with an international suit and they are more willing to speak English. In France, l'homme d'affairs, businessmen, do love to speak English, so do the cafe waiters and waitress in their penguin suit! Though it might be politically incorrect to request BBC English from every lips and tongue, the french just love their french accent when they speak English and they strive to keep their french trace, just like all spoiled kids love their milk moustache to remind you that afterall, they are kids!

12 October 2006

8 October 2006

Nessun dorma

This aria from Giacomo Puccini's (1858 - 1924) opera Turandot (1920-1924), was written in 1924 and premiered on 25 April 1926 in Milan with the Spanish tenor Miguel Fleta as the Prince, Calaf. However, it was Luciano Pavarotti (b.1935) who made Nessun Dorma famous!

Here is the version Pavarotti in live in Paris 1998 (12 July, one day after the French championed the World Cup and one day before their National Day). It was a pity that at (1'58" - 2'12") in the video, there should be two lines of chorus which was missing during the performance. It was definitely a producer's faut not to arrange choirs!

Click 2 times on the Play icon, please.

Courtesy: boellebent (Demark)

Nessun dorma! Nessun dorma! (No one sleeps! No one sleeps!)

nella tua fredda stanza guardi le stelle (in your cold room look at the stars)

che tremano d'amore e di speranza... (that tremble with love and hope!)

Ma il mio mistero è chiuso in me, (But my mystery it is locked in me)

il nome mio nessun saprà! (And my name,no one will know!)

No, no, sulla tua bocca lo dirò, (No, no! On your mouth)

quando la luce splenderà! (I will say it, when the light will shine!)

Ed il mio bacio scioglierà il silenzio, (And my kiss will break the silence)

che ti fa mia. (that makes you mine!)

Voci di donne (Chorus):

Il nome suo nessun saprà... (His name no one will know...)

E noi dovrem, ahimè, morir, morir! (And we shall have, alas, to die, to die...!)

Dilegua, o notte! Tramontate, stelle! (Disperse, o night! Vanish, oh stars!)

Tramontate, stelle! (Vanish, oh stars!)

Vincerò! Vincerò! (I will win! I will win!)

Here is another version performed by the famous Three Tenors, Plácido Domingo, José Carreras Coll and Pavarotti in Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles for the 1994 World Cup finals with choirs.

From the lyric, we know that it's not a sad piece of music, but the "heartbreaking" mood is in the melody. This is the opening song of Act III, when the Prince is singing alone on the stage, waiting for the sun to rise and for Turandot to love him. In the background, the Chorus' sombre repetition of Turandot's order that "No one in Pekin is allowed to sleep tonight, until his name is found out" is like a phantom besetting the Prince's hope, like the ghost of Lo-u-Ling waiting for her revenge. Though the prince is hopeful and confident in his words, the chorus lines remind him of the cruelty of Turandot, and his heart sinks (that's why I was upset with the Parvarotti 1998 version). The G major becomes the key signifying "dark hours before sunrise", inspiring the Prince's fear of a failing love and Turandot's terrified avoidance of a marriage with the unknown Prince. Love becomes a war, and everyone is agitated and sleepless tonight.

Turandot (1920 - 1924)

Turandot is the beautiful cold-hearted femme fatale Princess of anncient China, whoever wants to marry her

must answer her three riddles, either he succeed or he beheaded. In Act I, at night, when the moon rises, the unknown Prince, Calaf, was bewitched by her beauty when she first appeared in the balcony to give death order to the Persian Prince. Calaf stikes three times the gong posing himself as the suitor of Turandot.

must answer her three riddles, either he succeed or he beheaded. In Act I, at night, when the moon rises, the unknown Prince, Calaf, was bewitched by her beauty when she first appeared in the balcony to give death order to the Persian Prince. Calaf stikes three times the gong posing himself as the suitor of Turandot.Act II, Turandot explains in her famous aria In Questa Reggia that her ancestor, Princess Lo-u-Ling, was ravished and murdered by a foreigner, and now out of revenge she has sworn to never let any man possess her. She warns the Prince to withdraw, but he refuses. The Princess presents her riddles:

"What is born each night and dies each dawn?"

"Hope."

"What flickers red and warm like a flame, but is not fire?"

"Blood."

"What is like ice, but burns?"

"Turandot!"

The Prince suceeds and it's Turandot's duty to marry him. Turandot get angry and pleads her father / Emperor not to leave her at the unknown Prince's mercy. The Prince offers her his riddle, "Bring me my name before sunrise, and at sunrise, I will die."

Act III opens with Calaf's Nessun Dorma with the distant repetition of Turandot's order to search for his name. Calaf's maid, Liu, is tortured by the soldiers for the Prince's name. Liu, who loves the Prince, sings, "The name that you seek I alone know." Turandot demands it, Liu answers, "Love", and suicides. Terrified by Liu's suicide and Turandot's cold-heartness, the crowd withdraws leaving Calaf and Turandot alone on stage. Calaf tries to convince Turandot to love him but in vain. He holds her and kisses her, and she feels herself turning towards passion.

Finale: Dawn is breaking, Turandot approaches the Emperor's throne and declares, "His name is .... Love!" (Curtain falls)

The beauty of the Opera is in the enigmatic and poetic of the 3 deadly riddles and the final resolving riddle. Wasn't Puccini irrational in the Prince's dumb move of posing the last riddle to Turandot and giving her a chance to escap and chop off his head?

Well, Calaf doesn't say "Guess my

name or you will die" but "Bring me my name and I will die". He actually wants to lose the game since whatever Turandot guesses, it would just be his name. He wants to marry her, of course, but he wants to defeat her cold-hearted defensiveness and have her fall in love with him. He will then die, in the sense of loosing himself completely to her and her love.

name or you will die" but "Bring me my name and I will die". He actually wants to lose the game since whatever Turandot guesses, it would just be his name. He wants to marry her, of course, but he wants to defeat her cold-hearted defensiveness and have her fall in love with him. He will then die, in the sense of loosing himself completely to her and her love.In Nessun Dorma, Turandot hasn't yet figured out all this love poetry business, and still thinks that she just has to get someone to reveal the Prince's name and then she can chop off his head. So she puts out a decree that no one in Pekin is allowed to sleep until the name is revealed.

When Puccini wrote the opera in 1902, it was a period of vexed relationships between China and the Western powers. In Europe, people were fascinated with Chinese art and culture at the same time, afraid of its "barbarism". Puccini's creation of a cruel Turandot while employing the beautiful Chinese folk songs as the musical themes for the opera is a classical love-hatred Western reaction towards China at turn of last century.

According to a interesting musicology study by Johathan Petty and Marshall Tuttle (2001), the Key signature is highly symbolic in the Opera. Throughout Act I, Puccini emphasizes Calaf's D Major (D) as leading tone to Turandot's E Flat Minor (Eb). This is a symbol of a definitive phallic threat from D which she seeks to deny. This threat is made explicit when Calaf rings the gong in D major, releasing energy that abducts Turandot's motif, and incites the Prince to modulate upward into Eb, signifying his surrender to Turandot's imperious beauty, as well the Moonrise and the position of Turandot in the highrise balcony.

In Act II, the solutions to Turandot's 3 riddles occur to the key scheme of D-D-Eb, precisely consistent with the psychological drama of the opera. "Hope" and "Blood" riddles are sung in D, Calaf's signature, "Turandot" riddle is self-evident in the Eb signature.

Then Turandot takes the patriachal C Major to plead to her father, when he insists that she should obey her own law, she crawls from C major up one octave to her father's C.

In Act III, Nessun Dorma starts with the chorus in Turandot's Eb, accending to Calaf's D. The power axis is reversed and thrusts Turandot's Eb and Bb down when the principle melodic material of the aria arrives in D, having released itself from the power of the Eb. And the final climax achieved on the word 'vinceró' is on A, the key which conquered Lo-u-Ling's Fb minor.

Courtesy: FamiliaOrero (Argentine)

This is another version by one of The Three Tenors, Placido Domingo, with The Metropolitan Opera in 1988, here the chorus lines are back and the stage design is wonderful.

This analysis of Petty (2001) gives another aspect of how music articulate psychological changes in the characters. Such as in Nessun Dorma, it's so touch simply because there are some many contradictory moods and emotions going on at the same, they are beyond the description of words but music!

5 October 2006

Esquisses de Frank Gehry (2)

If the purpose of life is to leave trace in human history, the common men's trace presents in their offspring. From generations to generations, his gene passed on through birth and death, and he is remembered.

For an architect, his trace becomes ever-present in the imposing concrete. Be it a scar on your face, or the sacred water baptised on your forehead, you cannot escape its intervention. How big is an architect's ego? He wants a toy for his son, and he wants it to be the biggest, the tallest, and the most long-lived. Look at those most wanted architects today who are building their pantheons at every corner of the world, aren't them the men dispersing their sperms and gene in the planet earth?

Imagine yourself happened to be born a Haussmann in Paris or a Gaudi in Barcelona, would you not walk with a peacock's tail at your back? Whether what your great grandfather left for you is a labyrinth in Paris or a Cinderella's pumpkin castle in Barcelona, you have the biggest toy to marvel at. Only that your home is too small to store your toy!

In My Architect, the introduction reads, " Everyman knows Louis I. Kahn, except one, his son!" So, this illegitimate son looks at the best toys his father prepared for him when he was just some years old. He said to himself, "my father is a great man!" All hatred disappeared, father-son reconciled. How glorious his toys become!

Photo credit:

MY ARCHITECT, Nathaniel Kahn, © 20003 Louis Kahn Project, Inc.

4 October 2006

One Note Symphony

Concert - Contemporary Music

04 October 2006 22h20-22h55

Grande Salle, Centre Pompidou

Click at the "Play" icon, 2 times... please!

3 October 2006

Love at the last sight - A director's (almost) true suicide

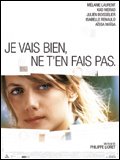

Je vais bien, ne t'en fais pas (2006)

1h40min

Director: Philippe Lioret

Screen writer: Philippe Lioret & Olivier Adam

Adaptation: Olivier Adam

With: Mélanie Laurent, Kad, Julien Boisselier

This is the type of film in which the scenarist kills the director, and since the scenarist of the film is also the director, then it appears to me almost a true suicide.

95 mins out of the 100, you sit in front of the big screen, cursing the director, and at the last 5 minutes, you fell in love with him thanking him for inventing such a beautiful cinematic language.

You watch the movie as you look at a mirror fallen apart, pieces spreading on the floor, you ask the director, "why do you have to accumulate so many useless details? why you are not advancing your story? where is the focus? why you keep sidetracking?"

When you almost lose all your patience to stay in the cinema, the plot turned finally at the last 5 minutes and the climax builds up and falls sharp in the last 20 second, and the film is over! You flahsed back what happened during these 100 mins like a vacuum cleaner sucking up the broken pieces of the mirror, and you realized the most insignificant bits are the essential tissues of the film.

What a trick the scenarist has set up for the director!

2 October 2006

The first Sentence

如,假寶玉第一次看到林黛玉時說︰「這個妹妹,我見過﹗」

Why is the first sentence so important? As a person, s/he impressed you and this image stays with you the whole life. As a book, it catches your interest, and you can never put it down until the last page. This is the craftmanship of writing. A powerful first line is a strong blow to its readers, and you may fall in love with the writer immediately as you may fall in love with a person.

How the writers open their books?

Ernst Hemingway starts from nowhere with this sentence: "Then there was the bad weather" in A Movable Feast. It was like a trap, you found yourself standing at the middle of the universe, across time, across geographical boundaries, without time without boundaries, because he breaks away from the rule of time, space and people.

Similarly, 莫言 in【生蹼的祖先們】 has his first character coming to the scene from nowhere, and the air is suspended, intriguing the readers to dig into it like a grave digger, "第二天凌晨太陽升起前約有十至十五分鐘光景,我行走在故鄉一片尚未開墾的荒地上。……我正在心裡思念著一個打過我兩個耳光的女人。我百思難解她為什麼要打我,因為我和她素不相識。」

Another way of open the scene is to start with an action, and this action is as banal as possible, but later you will see it as the core of the whole story. In Mrs Dolloway, Virginia Woolf starts with "Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself". This was a bomb to the literary scene when the book first appeared in 1925, not just in the sense that it focuses on a one-day-activity of Mrs Dolloway, but also the writing and this first sentence, which is so trivil that it bypassed the rhetorical announcement of all classical writings.

Talking about the great classics, nobody can forget the famous opening line from A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens. "It was the best of times, it was the worst of times..." (see comment for complete quote). The power of this long first sentence is the doubleness, the pairing up, which was the theme and the structure of the novel, including London and Paris, Sydney Carton and Charles Darnay, Miss Pross and Madame Defarge, etc.

In Living to Tell the Tale, Gabriel Marquez starts with "My mother asked me to go with her to sell the house." and then the journey to sell the house evolved the story. The first paragraphy of the book is amazing, a friend said to me, "this is what makes a writer!" Yes, it's a beautiful paragraph, I am willing to be Marquez's typist for one time. Here you go:

"My mother asked me to go with her to sell the house. She had come that morning from the distant town where the family lived, and she had no idea how to find me. She asked around among acquaintances and was told to look for me at the Libreria Mundo, or in the nearby cafe, where i went twice a day to talk with my writer friends. The one who told her this warned her: "Be careful, because they're all out of their minds." She arrived at twelve sharp. With her light step she made her way among the tables of books on display, stopped in front of me, looking into my eyes with the mischievous smile of her better days, and before I could react she said: 'I am your mother.'"

How did I start my book? My first sentence is:

當時,奶奶是這樣對白妹說的︰「俺厝地址是福建省晋江縣陳埭鎮岸兜村前街祠堂邊第三塊厝。」